ASSEMBLY 2

In the epic blizzard of December 2022, Assembly lost power for nine hours. Without heat the pipes and fittings in its fire protection system froze and burst. Unable to reopen without resolving the damage, Assembly officially closed to visitors to undertake a full building assessment and analyze its options. With quotes to repair the fire suppression system coming in over $100,000 and no quick fix on the horizon, the decision was made not to try to reopen Assembly 1: Unstored, which was subsequently deinstalled, with the works returning to the artists.

When Assembly first opened its doors to the public in the spring of 2022, it seemed such an unambiguous triumph: an ideal case in the creative reuse of distressed real estate, resource matching, and civic renewal. Here was a spectacular but long defunct space reclaimed to display a type of work that many artists have in storage (large and difficult and therefore institutional) that would otherwise go unseen, for the benefit of a distressed community. But, in a storyline that is becoming the global rule rather than the occasional local exception, nature has taken to exposing the fragility of our assumptions. With its vast, airy, almost natural-seeming open space, Assembly is a perfectly sympathetic environment for showing art. But that is not the same as being a perfectly suitable space in which to safeguard it—at least not in a supercharged climate.

The calculus of responsibility and care having thus changed, Assembly 2 could be described as a holding action organized under the banner of self-insurance. The works are still ones that would otherwise be in storage, but everything now on view was made by and belongs to Assembly’s artist-founder Bosco Sodi (b. 1970). With only his own work at risk, Sodi takes a different view of Assembly’s imperfections as an art storage space.

Being made in collaboration with nature and comfortable with all of the vulnerability to chance and change that requires, Sodi’s work tends to center imperfection and contingency. So intrusions of rain, sleet, and snow, massive temperature variations—often in the same day, from one side of the space to the other—and excoriating rays of direct sunshine, make it not only not inhospitable, but an ideal environment for the presentation of his work. And that is how Sodi got himself into this wonderful mess in the first place.

–Dakin Hart

BOSCO SODI: STUDIO STORAGE

Main Gallery

Rotating works from storage, this refresh of the main gallery space shows the range of Sodi’s painting and sculpture, with the focus on large canvases in black and white and spheres and cubes in clay.

ADRIÁN S. BARÁ AND CORBAN WALKER

Focus Gallery

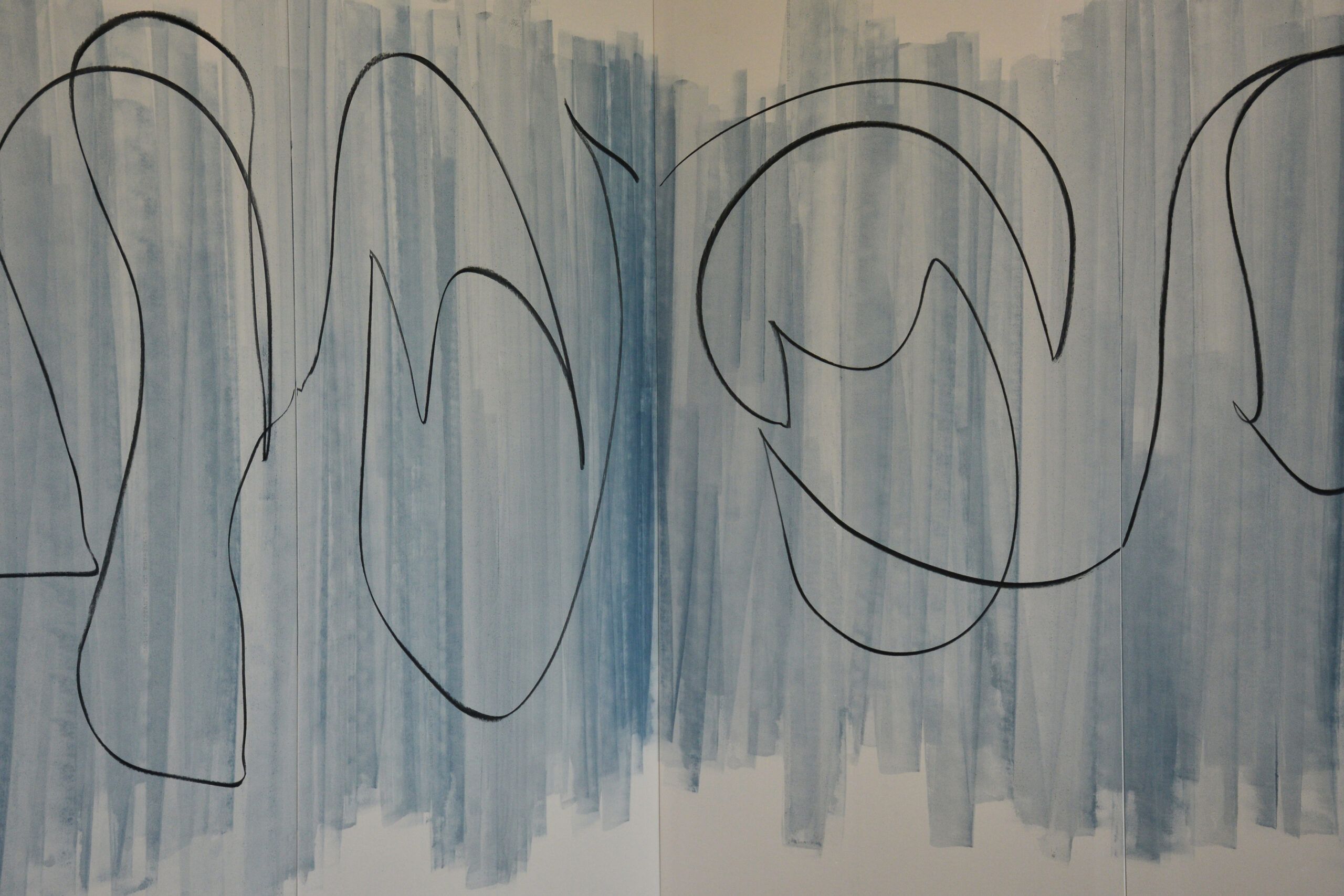

The intervention of Adrian S. Bará, Music for Changes / Music for Changes, painted indigo on drywall, poses a temporary tension between the ancestral practice of dyeing based on the Jiquilite plant, to obtain the indigo color, and the prefabricated plaster panel , of daily use in contemporary architecture. On this support, his large-format drawing suggests a bodily and choreographic gesture but also musical and urban graphics.

“Corban Walker Bosco’s Grid” is part of a series of acrylic sculptures made between 2012 and 2022. Over the decade, he used the extruded amber material (sometimes mixed with other colors) to articulate his perception of scale, derived from a visual height of 129cm. He combined an organization of rules with his physical orientation. The mathematical rules analyze such variables in condensed formations, while deliberately stretching the capacity of assemblage and one’s perspective of gravity.

He is interested in the contradiction of fabricating transparent sculptures that present a partial view of its entity. Experiencing a partial engagement with an object or overcoming an obstructed views by structures found in a defined space are arenas for how we respond to physical environments, in very specific ways. This body of work provides a means for navigating a room or space with an added awareness of viewer’s own presence.

BERNAR VENET

Out Front

Indeterminate Hypothesis continues the artist’s lifelong, process-based investigation into the mathematical and philosophical implications of the line. A contemporary of Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and Sol LeWitt, Venet has concentrated his artistic practice on the complex relationship between an object’s conceptual framework and its materiality for over six decades.

The five abstract Indeterminate Lines consist of spiraling rolls of steel that sit, balanced or stacked in novel compositions, on the gallery floor. As well as manifesting the concept of the line as an object—playful, antic, and unpredictable—the series from which these works emerge explores and demonstrates the limits of material resistance. Venet’s physical manipulation of raw bars of steel into unscripted configurations of between one and six elements demands gargantuan effort and reveals the relationship between artist and material as both a collaboration and a battle of will. The resulting configurations of tightly wound, inextricable loops of industrial material “open a doorway to fundamental principles such as indeterminacy, chance, accident, unpredictability, chaos and, even, incompleteness,” says the artist.

Bernar Venet first gained recognition in the 1960s for the development of his Tar Paintings, Cardboard Reliefs, and his iconic Pile of Coal, the first sculpture without a specific shape. The year 1979 marked a significant turning point in Venet’s career: having recently begun a series of wood reliefs—Arcs, Angles, and Straight Lines—he created the first of his Indeterminate Lines and was awarded a grant by the National Endowment for the Arts.

With 9 Acute Unequal Angles, Venet persists in his argument and went so far as to assert that science and mathematics were to become the content of his work. Drawing a straight line was not interpretive. It was not a lyrical expression about surface space. For Venet, it was more about the line itself. The artist’s recent large-scale steel angles seem consistent with arcs in that they are arranged in groups, often close together, with random spatial intervals, almost always with the same number of degrees within the acute angle as within the circumference of a circle. One could say that this has always been the question Venet has sought in his work, even as the question perpetually moves through various angles of vision.